Volume 4, Issue 1

Poetry

including work by Cyrus Cassels, Candice Kelsey, Ellen June Wright, Bailey Quinn, and more

Salvador Espriu translated by Cyrus CassellsSong of Triumphant Night

Where the gold slowly ends,

flags, unfurling night.

Listen to the roar

of countless waters

and a wind opposing you:

unbridled horses.

When you hear the hunter’s horn,

its bold blast,

you’ll be summoned forever

to surrender to dusk’s kingdom.

An ancient, deep-rooted pain

that has never known dawn!

After the Trees

When I can no longer lose myself

in lush snow, an acolyte

of lights and the clashing horizons

looming above

my country’s imperiled trees,

I’ll know the wanderer’s bone-deep weariness

for the bonanza

of a home-place and fountain,

exhilarating smells of earth

and sliced bread set on the table.

Then, unchained at last

from fear and hope,

I’ll lull myself to sleep forever,

listening to the slow

sound of hoes in broad fields,

the rustle of dusk

among the vine-tendrils.

Salvador Espriu (1913-1985) was Catalan Spain’s most venerated 20th century man of letters and its main contender for the Nobel Prize. After a sickly childhood in which Espriu was seriously ill for two years, he began publishing short stories and novels during the early 1930’s. During that same period he studied history and law, and was on the verge of taking a degree in classical languages when the Spanish Civil War erupted. He was then drafted into the army and served until 1939. Espriu’s first book of poetry, Sinera Cemetery, was published in an underground edition in 1946. Like many of his stories, it depicts the small village of Arenys de Mar (Sinera), his parents’ hometown in the Costa del Maresme, a little north of Barcelona, where the poet had spent a fair amount of his youth. Espriu’s poetry wed political critique and denunciation with a brand of austere lyricism and often brooding, death-obsessed imagery, as the flame-keeping poet prevailed, despite Franco’s long, truculent ban against the public use of Catalan. He fashioned a series of parallels between Jews and Catalans, whom Espriu felt were exiled from their collective identity even while they remained in their own land. 2013, the hundredth anniversary of his birth, was declared “The Year of Espriu” throughout Catalonia.

Cyrus Cassells, the 2021 Poet Laureate of Texas, is the author of nine books of poetry, including Soul Make a Path through Shouting, The Gospel according to Wild Indigo, and The World That The Shooter Left Us, (Four Way Books: 2022). He is the translator from Catalan of Still Life with Children: Selected Poems of Francesc Parcerisas, which garnered the Texas Institute of Letters’ 2019 Souerette Diehl Fraser Award for Best Translated Book of 2018 and 2019. His honors include a Lannan Literary Award, a Lambda Literary Award, the National Poetry Series, an NAACP Image Award nomination, and the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Award. He is a tenured Professor of English at Texas State University.

Candice KelseyAerodynamic Lift

Candice Kelsey [she/her] is a poet, educator, and activist in Georgia. She serves as a creative writing mentor with PEN America's Prison Writing Program; her work appears in Grub Street, Poet Lore, Laurel Review, and Worcester Review among other journals. Recently, Candice was a finalist in Iowa Review's Poetry Contest and nominated for Best Microfiction 2023. She is the author of Still I am Pushing (FLP '20), A Poet (ABP '22), and a forthcoming collection with Pine Row Press. Find her @candice-kelsey-7 and www.candicemkelseypoet.com.

Adrian SilbernagelAmerican Dream

Humid June. Hair of the dog. Nostalgia

a dripping faucet in a global water crisis.

My roaring twenties were eclipsed

by a great depression: 35 and still drinking

the dregs of dreams of power lines, dance

clubs, and speed. A burned out carnie

speaking Cant, his dead native anti-language.

Richard Dawkins delivers the Narcan.

I wake up in the aftermath, pipe dreams leveled

except for this old carousel I now operate

with only fleeting reprieves from the grind

of the gears, the remainder of my sum.

And when the youth caw about revolution

I’m the first to feel the rumble, like a moth

atop a tower just before it crumbles.

Adrian Silbernagel is a poet and activist from Fargo, ND. Adrian now lives in Louisville, KY, where he and seven other queers operate a worker-owned coffee shop. Adrian writes and facilitates workshops for QueerKentucky, a local LGBTQ+ publication and consulting service. Adrian has published two books of poetry: Transitional Object (The Operating System, 2019) and Late Style (Nanny Goat Books, 2021). Visit Adrian's website.

Peter SerchuckCar That Can’t Resist a Wall

We’re driving as fast as we can

on the road called Great Tomorrow.

Road signs rise up like ghosts to shout

warnings, but we ignore them.

Bullets fly past the windshield

whistling God Bless America.

There are fires in the rear-view mirror;

but that’s so yesterday’s news.

It’s been raining for days, but why worry?

The good lord promised no more floods.

People by the roadside flag us down

but we know how to blur their faces.

The radio screams, Stop! Go back!

so we turn the dial to Elvis.

We’re diving as fast as we can

on the road called Great Tomorrow.

When we close our eyes we can see

a future nobody will forget.

Peter Serchuk’s poems have appeared in a variety of journals including Boulevard, Denver Quarterly, Poetry, New Plains Review, North American Review, Atlanta Review and others. He is the author of three published collections: Waiting for Poppa at the Smithtown Diner (University of Illinois Press), All That Remains (WordTech Editions) and, most recently, The Purpose of Things (Regal House Publishing). He lives on the Monterey Peninsula in California. More at peterserchuk.com.

Lulu LiuThe problem with talking about physics

Aspens doing something in the wind.

— Robert Hass

Then, when finally we were

no longer hungry, talk

turned to the end of the Universe.

The kitchen light hummed. Your hand

turned, lifting

and placing things on the table, and we

felt as near to oblivion

as a pile of kindling. You

wanted to know how it will end,

all this, so we huddled around

the three topological

infinities, and I struck

the match.

Light and murmur, time

like the head of a cauliflower,

maybe. You laughed. You were enchanted,

but I felt as ashamed of your

wide eyes as

if I had told you a lie.

Badly, I wanted to feed you wonder

in that tiny pill.

To say even the word, infinite,

it’s too easy-

and too provocative, and

you were enchanted, but I felt

as dull as cloth: as if I had

picked up your oranges from the bowl

and juggled them — ta-da–

I’m sorry. There is real

wonder. And sometimes I do

feel that wonder, too. Sometimes

I look into that dark hole

sky and I know that your God

is my infinite. But, no, I can’t

tell you more. I don’t

know what any of it means.

Lulu Liu grew up on the East Coast of the United States after moving from her birthplace in a rural part of western China. Currently, she is a writer and physicist, and lives between Somerville, Massachusetts and Parsonsfield, Maine. In that period when she considered making writing a career, her reporting and essays appeared in the Technology Review, and Sacramento Bee, among others. For the time being, however, she is content pursuing her interest in deep space exploration as primary occupation. You can find more of her poetry in Apple Valley Review, Rust + Moth, boats against the current, and Thimble. She's grateful to be nominated for Best of the Net 2023.

Emma Jahoda-BrownEast West Highway

One year with two afflictions. The hemispheres of

Guilt and relief. I list the good things each morning.

The cicadas crisp shells cling to the fence.

I have been more than one person.

My heart is surrounded by water.

I have a small anger when he talks to me

From which I can grow

The ore of compassion.

I smash bags of ice on the kitchen tile.

Peel garlic and ask for forgiveness.

For pleasure, unearned.

For growing quieter

The wind rattles the shower curtain on its hooks.

At six am he lumbers into another room.

His language is sliced fruit.

When I attempt to speak

The machine says did you mean representative.

Our conversation is put through a sieve.

The swallows come profusely from the barn.

Asterisks of daylight, graphite

coming loose from the page.

Emma Jahoda-Brown is a writer and photographer. She holds a BFA in photography and media from California Institute of the Arts and an MFA in poetry from Columbia University. She splits her time between New York City and Los Angeles.

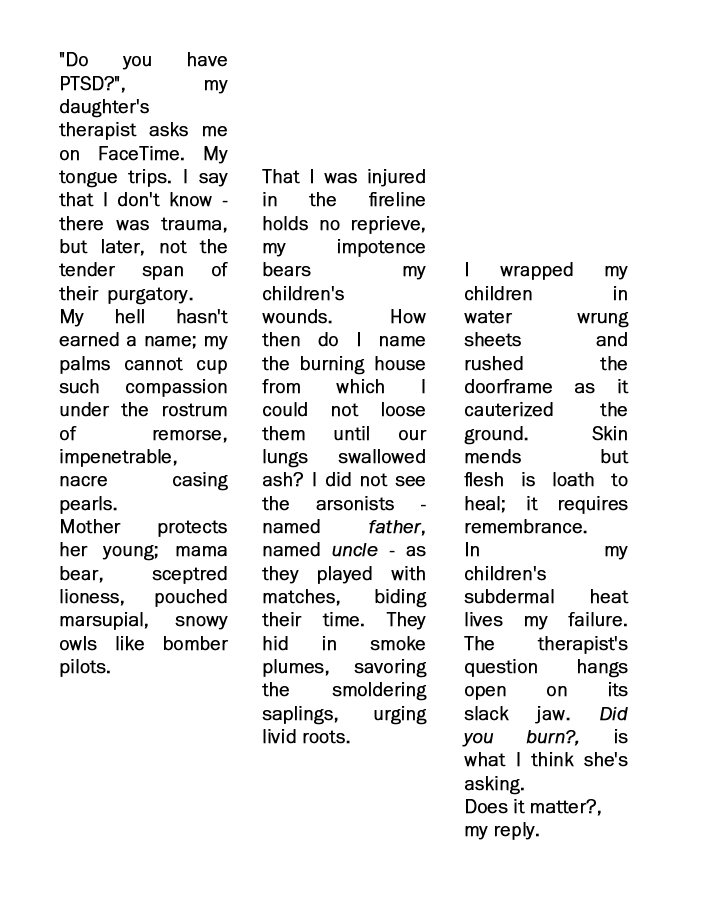

Lisa DelanC-PTSD

Lisa Delan's work has been featured or is forthcoming in American Writers Review, Burningword Literary Journal, Cathexis Northwest Press, Passengers Journal, Poets Choice, The Pointed Circle, Viewless Wings, Wild Roof Journal, The Write Launch, and other publications. She has been nominated for a 2023 Pushcart Prize. When she is not writing poems, you can find the soprano, who records for the Pentatone label, singing art songs by American composers on texts of many of her favorite poets.

Rebecca IreneWeigheth

Though art weighed in the balances,

and art found wanting. —Daniel 5:27 KJV

Weigh the bread.

Weigh the calf.

Three-square-meals-a-day, but some girls choose to feast on cotton balls

soaked in orange juice to stay thin. How strange the machines of sustenance.

Nights, I serve women who barely eat—scrape leftover food from thirty-dollar

dishes into the garbage. Risotto, polenta, foie gras, crudo, veal, salmon, & venison.

Weigh the diamonds,

& loaded dice.

It’s true. Waitresses judge what customers consume, & their wedding rings.

Maybe we can’t help it. It’s our job to take note of what’s not eaten, & hands

are omnipresent during most of dinner. I would say diamond size doesn’t matter,

but like everyone else working for tips, I sometimes lie. I want the sparkle, covet

the weight of a spouse’s yearly salary wrapped around my chosen flesh. V guffawed

that the diamonds I drooled over were probably fakes. She also considered even odds

a pipe dream. Face it, she grinned, some are destined for 5-carat, others 10K gold-plate.

Weigh the apple.

Weigh the snake.

V refused to believe it was an apple in the garden of Eden. Convinced it was a pomegranate,

she blamed John Milton, specifically, for perpetuating the fruit lie, as she called it, paraphrasing

Paradise Lost at every opportunity. It didn’t matter that Milton had never actually used the word

apple. When I argued he had only called the forbidden fruit fuzzy, & acutely juicy…wasn’t there

a possibility he was implying peach, V crossed her arms, sighed that I understood very very little.

Weigh the naughty

& nice.

Femme fatale is more pleasurable to say than the girl next door.

(& frankly just more pleasurable. Period.) The former has often been

the latter, but rarely the other way around. Once one visits Paris, it is difficult

to return to cribbage, & baking cookies in a small town. If a femme fatale somehow

does become the suburban woman next door, chances are she believes past regrets can

be atoned for by good behavior, & random gestures of kindness. She wears an apron, always

pays the toll for the car behind. V once asked if I was still waiting tables because I felt guilty

for previous behaviors. My beautiful martyr, she whispered whenever I crept in after midnight.

Weigh the want

& worthy life.

Perhaps we will be remembered by what we most wanted, but were unable

to get. Or judged by what we decided wasn’t worth the price of having/keeping.

Does love always imply sacrifice? Whenever someone asked V how she was doing,

she replied better than she deserved. We discovered gratitude late in life. Some days,

it was almost enough to save us.

Rebecca Irene is a poet, editor, and performance artist based in Portland, Maine, land of her ancestors. Creative obsessions include scriptural mandates for women, the impact tipping practice has on self-esteem, female invisibility/immobilization after forty, ocean tides, and cicadas. She believes art can shatter paradigms of worth, and that you can simultaneously be a dog and cat person. Her poems are published in Spillway, Parentheses Journal, RHINO, Carve, and elsewhere. She was named the 2020 Monson Arts: MWPA Poetry Fellow. Poetry Editor for The Maine Review, Rebecca holds an MFA from VCFA, and supports her word-addiction by waitressing. Find her online at www.rebeccairene.com.

Susan Michele CoronelMy Younger Daughter Resists Tradition

She tells me one day I don’t want to take Yiddish

classes anymore. In Fiddler on the Roof,

the youngest daughter insists on leaving the fold

because of true love, but to her father

she’s a splinter in a cantaloupe, untethered

from tradition & from every family who has ever said

stay, follow, without doing it themselves.

True love: a violin shivers naked, trills on a hill,

attempting to play a familiar tune. But the music escapes

through holes in pockets, beguiles even those

with the best intentions, singing, Look

what you’ve done. Loss is a bone caught in the throat,

a sewing needle threaded not once

but in both directions. The only Jewish tradition left

for my daughter is food: matzo ball soup, chocolate coins,

herring drowning in sweet onions & cream.

What she does not know is that I am trying

to keep my balance on a roof whose shingles dangle

like warped leaves. There are no prayers of devotion

but reams of remorse, the repeated desecration

of our culture through history confirming

that we still sit on rotten hands. I care nothing for the temple,

empty rituals opening like a can

of preserved peaches, but yearn for the parsley sprig,

for the Star of David to be twisted & reimagined

so my children will not lose what came before

without knowing what they’re losing, even as I know

it’s already lost forever. Love is sweet but better

with a bisl of salt, a kiss on the punim.

Thieves & the dead I’ve loved knew darkness

like a tattered coat. Children always refuse,

but it’s still better to ask them to carry something

than to come to the table of the future empty-handed

Susan Michele Coronel lives in New York City. Her poems have appeared in numerous publications including Spillway 29, TAB Journal, Inflectionist Review, Gyroscope Review, Prometheus Dreaming, and One Art. In 2021 one of her poems was first runner-up for the Beacon Street Poetry Prize, and another was a finalist in the Millennium Writing Awards. In the same year, she received a Pushcart nomination and was longlisted for the Sappho Prize. Her first full-length poetry manuscript was one of five finalists in Harbor Editions' 2021 Laureate Prize.

Bailey Quinnin the house where god lives

after Terrance Hayes

in the house where god lives crooked back

unpainted fingers cracked bare lips She prays

calla lilies and pale lace stitched behind

her eyes in threaded vines She blames

her shame on hips wide like a running river

men dive uninvited brazen they chide wanton trills

define her song discordant notes provoke her

catacomb hymns coat the back of their throats

broken bread they blessed on unspun doilies

devouring beauty in vain her open veins

stained black florid violets swaying whispers

in caves echo: violent, silent, women before

her, shame. in the house where god lives She is

praying in the house where god lives She is prey.

EVP Session in the Basement of My New Home

Bailey Quinn (she/her) is currently pursuing her Master of Arts in English at Weber State University. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Emerson Review, West Trade Review, and Sand Hills Literary Magazine, among others. You can find her on Twitter @baileynquinn.

Ellen June WrightTime’s Traveler

(for Angela, enslaved, Jamestown, Virginia 1619)

If I could sail on currents / of minutes, hours, days and years in reverse / and find myself upon the eastern shore / by the old settlement / and watch the man-of-war lower anchor / watch the light and dark passengers / climb into the dinghy and descend / row towards the sand / if I could be there to watch the 20 plus ‘Ngolans / groggy from months at sea / eyes full of wonder at this strangeness/ place their feet upon land / then collapse / I would fill my arms with each and every one / like a Charles White woman or great mother holding her children / and I would wipe their faces / each one with a warm cloth / remove the blood and the briny seawater / the way a midwife welcomes a babe / just from the womb / even as she knows what the world is.

Let me whisper even as I hear

a dirge of jazz clarinet and saxophone,

playing for you.

This is not Gilead.

There is no balm here.

You will have to salve

your own wounds.

You will have to be your heart’s

own Promised Land,

Ellen June Wright was born in England and currently lives in Northern New Jersey. She is a retired English teacher who consulted on guides for three PBS poetry series. Her work was selected as The Missouri Review’s Poem of the Week in June 2021. She is a Cave Canem and Hurston/Wright alumna and received 2021 and 2022 Pushcart Prize nominations.

Emily Lake HansenWOMEN WITHOUT A COUNTRY

after Eavan Boland

These days I’m a poem in a person costume. I mean nothing

romantic: flies buzz fragments of memory, frogs chirrup

over an empty lake. I come from a long line of women

without a country. From Ukraine to Canada to Jersey

how did my mother end up in Orange Beach burninga

home onto her body with baby oil? How did I come

to this Americana: red & white checkered tablecloths,

a flag of spongy white cake. There is so little

of a home inside me. You’re America, my mother sang

Amazing Grace, the National Anthem, crying at the reach

of her own notes. No one is alive to tell me when

this hunger & madness started, the binge & purge

of our womanhood. By the fourth grade, my mother

wore a size 9 shoe, had to choose between high heels

or work boots. At age 9, my favorite animal

was the sea. I thought I’d live in California forever.

I wish I could say I’m different now, but that would be

a lie no more or less than this one. Of the 8 living women

descended from my grandmother, 8 out of 8

are crazy. We bake rolls of beer on our breath, rolls

of history in our bellies. If memory isn’t an accurate

mirror, I am sorry. To heal is not to say it didn’t happen,

but to make something from what remains.

Emily Lake Hansen (she/her) is a fat, bisexual, and invisibly disabled poet and memoirist and the author of the poetry collection Home and Other Duty Stations (Kelsay Books) as well as two chapbooks: The Way the Body Had to Travel (dancing girl press) and Pharaoh's Daughter Keeps a Diary (forthcoming from Kissing Dynamite Press). Her poems and essays have appeared in 32 Poems, OxMag, Pleiades, Up the Staircase Quarterly, So to Speak, and Atticus Review among others. A PhD candidate at Georgia State University, Emily lives in Atlanta where she serves as the creative nonfiction editor for New South and teaches first-year writing and poetry at Agnes Scott College.

Meredith BoeLeo Season

Somewhere, an infant cries, maybe dreams, and no one agrees on what the cloud shapes should

signify. Jesus, animals, war. Pesky nostalgia that’s too severe to recollect. People are turning 30

in batches and patience is out the window. The air hints of burning, but no one necessarily dies

and no piles of ashes materialize. The distance between 30 degrees of celestial longitude is

smaller, by far, than the space those internal infernos occupy, only visible to those with earthly

crowns. One toothy yawn and the world they’ve known, every set of longing eyes, shivers. Oh,

I’ve heard this story before. Someone once told a lioness she was a predator. She replied, Every

moment is a masterpiece. Wherever your mind goes when you hear that song

Meredith Boe is the author of the chapbook What City, which won the 2018 Debut Chapbook Series Contest from Paper Nautilus. She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2022, and her work has appeared in Newfound, Another Chicago Magazine, Chicago Reader, After Hours, Mud Season Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago and contributes to the Chicago Review of Books.

Cecilia SavalaCARDIO (n.)

When you loved your brother’s best friend; when you ran track in high school. Traveling at three

feet per second—a marathon in twelve and a half hours. A town in Greece—a battle in 490 BC.

Sounds like—it doesn’t get easier, you get stronger. Femoral if you’re brave. Athletes measure in

volumes and breathe—in 4:4 time—literally, the after-shape. The before is all huffs,

riffs—sporadic. The foot is measured in falls. To cause muscle-wasting (adj.); on the road to

skinny fat. There’s no such thing as spot reduction—ask your core to do the counting. Root:

connected to the—leg bone. From the Greek science to mean—to speak of the thing. Timing

yourself to do the math later. When you were a competitive eater. When you hated yourself

enough to outrun yourself—in spikes in neon in miles. Look at the calves on that one. The

shuffle—the roundabout. Let me count the ways—elevation, speed, a crush, devotion, carb up,

sprint, one-night, all night, overnight, pacer, altitude, dopamine high—committed—to go the

distance or tread in place—hottest where the blood is closest to the surface

Cecilia Savala is originally from the Midwest but is currently making her home in Tempe, AZ where she is an associate editor of Hayden's Ferry Review. Her work can be found or is forthcoming in The Boiler, Swamp Ape Review, and Barrelhouse, among others. Follow her at @cecsav on Instagram.

Kenneth JohnsonMoon Rabbit

There is a rabbit making tortillas on the surface of the moon. You can see it, if you look

closely, as it stands over a comal heated using batteries from an abandoned go-kart.

Lately, it has been thinking about installing solar because it’s eco-friendly. It makes tacos

on Saturdays to avoid being called a cliché. For special occasions, it makes tortillas

pintadas with images of skulls or birds. It is said it saved a man on earth who later

became a god. Now, Moon Rabbit can live on the moon rent free forever. On holidays, it

makes tamales with salsa verde and tres leches cake for dessert.

Kenneth Johnson is a poet, visual artist, and educator living in Claremont, California. He likes to think his visual art and poetry are reflections of one another-- they include myriad subjects, from the mundane to the conceptual. His poetry has been published in Carousel, Hitchlit Review, The Diaspora/UC Berkeley, and other publications.

Anthony Procopio RossSecurity

Anthony Procopio Ross serves as a Poetry Editor for deadpeasant, a counter-cultural literary magazine of arts and writing located in KCMO. Anthony's poems appear in the McNeese Review, the Laurel Review, Bear Review, The Inflectionist Review, and others. An Andreas Creative Writing Fellow in 2021-22, he read his work with Ross Gay at MNSU, Mankato. He has led creative writing workshops for adults with developmental disabilities, learning and growing with Cow Tipping Press. Currently, he teaches writing in and around KCMO.

Sara BurgeTalk Show Haibun

My ex calls from Chicago to see if I’m watching the Jenny Jones Show. It’s the 90s. Outside, the

forest looms within its nakedness. I’m about to be quasi-famous. He pleads through the screen to

understand why I left. Jenny wants to know why, too. No one asked me. Stock footage of a plane

represents him fleeing Missouri. I crushed him so savagely. Thank god he didn’t give them a

picture of me. Thank god this is pre-social media. Outside, the forest can’t crawl from its brown

husk. He purrs with one of the girls on Jenny’s stage. I’m happy for him. He introduced me to the

Dead Kennedys. Helped me do my taxes. Made sure the old folks in his neighborhood didn’t

suffocate in summer. But he also used talk shows to broadcast personal situations. That’s one

reason why I left, I would have told Jenny Jones if she’d asked. Outside, the trees try to speak.

Their mouths fill with wasps. Later, his mother will call my mother to say I make him sad. She’s

worried he’ll hurt himself. We shouldn’t speak again. We never do.

Stock footage flickers.

No one has died this winter,

though there’s always time.

The Call Is Coming From Inside the House

I won’t say Bloody Mary

three times in a mirror

or Candyman Ed Gein Bundy

I won’t say Zodiac Night Stalker

Speck I won’t say Boogeyman

Bell Witch Spook Light

Bride of BB Highway

I won’t say the name

of that babysitter

who held my hand

over the stove because

he said I told a lie

I won’t say

cholesterol trans fats processed meats

I will say One more drink

I won’t say cancer lay-off

dog bite or car crash

anxiety heavy cream

I won’t say shortness of breath

heart attack dementia

when I stare too long at nothing

or forget a good friend’s name

I won’t say We should meet this week

I will say I’ll quit smoking

next week because who can say

because the killer’s always

in the back seat

Sara Burge is the author of Apocalypse Ranch (C&R Press) and her poetry has appeared in or is forthcoming from Virginia Quarterly Review, Prairie Schooner, The American Journal of Poetry, Pacifica Literary Review, Cimarron Review, River Styx, and elsewhere.

Zackary MedlinBleeding Mycena (M. haemapotus)

the tree isn’t a tree yet

it is a body stretching out

its hands towards others

the bodies aren’t bodies yet

they are children molting

their bones are shredding

their hands their hands

are twigs shedding skin

the children aren’t children

yet they are stick figures

braiding stick-figure-fingers

into limbs the smallest

twigs needle into the others’

arms until the bodies are

saplings leaning into one

another being stitched

together into a single black

gemel a rot runs deep

beneath the bark tarry sap

dripping from a tree-tap’s

septic spout saprophytic

mycena sprout like bloody gills

hungry to inhale their own

putrefaction molasses-thick

cat-piss-ammonia stink

one of the diminishing voices

knotted in the tree will say

“hey at least i’m still a fungi!”

the tree will fall down laughing

the rings of children inside

will laugh themselves to death

Zackary Medlin (he/him) grew up in South Carolina, ran away to Alaska, tried his luck in Utah, and now lives in Colorado, where he teaches creative writing at Fort Lewis College. He is the winner of the Nancy D. Hargrove Editor’s Choice Prize, the Patricia Goedicke Prize in Poetry, and a recipient of an AWP Intro Journals Award. He holds an MFA from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and a Ph.D. from the University of Utah, where he was awarded a Clarence Snow Fellowship. His poetry has appeared in journals such as Colorado Review, The Cincinnati Review, Grist, and more.

David GoodrumSandpapered and Trimmed

he scuffs up fractured varnish

bleached grain and startles

he’s at Lewy’s Body Shop & Hardware Store

old Mr. Parkins helps him choose paint

mixes colors when asked for white

the latex turns to smoke

when it touches the stirring stick

another quick doze and eyes open wide a foot jerks

and arms waver as fingers grip the Lazy Boy armrests

he whisper-shouts towards where mom used to sit

Tell them I’m at our house fixing the kitchen!

then he’s downstairs rummaging

through the paint cabinet

searching for color charts spotting

turpentine in canning jars

looking for sandpaper and trim

sees the youngest slide

in socks down the back hallway

slippery with fresh wax

the middle son falls

off the roof sixteen years ago

breaking his collarbone

the oldest unable to drive

the single-family-car home from prom

wrecked

and the first-born daughter

desperate to leave home

leaps from high school into the nunnery

still in the hunt for a putty knife he clutches

headless paintbrush handles

given out to lure him

back to the store for free bristles

reaches deep in the cabinet for repair kits

finding only mineral spirits

his weekend cologne

he never leaves the chair which like his memory is in shambles

my own overwhelmed by his decline

if he ever read to me it is lost

and if he ever hit me it is whitewashed

we both now latch onto paint rollers hard as marble

shaking ancient metal paint cans

most stone silent others sloshing

heavy with memory aching for a pan

David A. Goodrum is a writer/photographer living in Corvallis, Oregon. His poems are forthcoming or have been published in The Inflectionist Review, Cathexis Northwest Press, Eclectica Magazine, Coffin Bell Journal, Spillway, Star 82 Review, The Write Launch, among others. His photos have graced the covers of Cirque Journal, Willows Wept Review, Blue Mesa Review, Ilanot Review, and Red Rock Review. Even before his early thirties, he was certain he would never write poetry again. He continues, it seems, to be wrong. About most things. See additional work, both poems and photos, at www.davidgoodrum.com.

Matt HohnerNote from an Adoptive Mother in a Baby Book, or Actual Results May Vary, with Addendum

You really cannot imagine how happy

you have made us. We waited for you

for a long time, and are so thrilled

that you are here. God has really

answered our prayers. I hope I will

be a good mother to you, and that you

will love us as much as we love you.

Even after I decide in ten years to leave

you, your father, and your younger sister

who your father and I will have three

years from now, for the toothless jerk who,

with his clueless wife, gave you a framed

image of Jiminy Cricket and Pinocchio

(how appropriate) for your coming-home-

from-the-adoption-agency present. I mean,

look, a mother can only take on so much

full-time accountability before she gets

bored and tired. My limit will be ten years.

That’ll be sufficient preparation for your

teen years and the rest of your life, right?

Things happen and people change, I’ll tell

you when you’re ten. I’ll reveal the whole

truth when you’re forty-eight. Anyway,

that’s the deal, and now I’m going out

onto the back porch to smoke a cigarette.

Matt Hohner’s recent publications include Rattle: Poets Respond, Sky Island Journal, The Cardiff Review, The Storms Journal, New Contrast, Live Canon, Passengers, Vox Populi, and Prairie Schooner. An editor with Loch Raven Review, Hohner has a collection Thresholds and Other Poems (Apprentice House) that was published in 2018. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

John SalimbeneThe Economy of Boyhood

“When I had no enemy I opposed my body.”

- Samurai Song by Robert Pinsky

My friends spent punches

like lunch money as kids,

printing purple receipts

all over our shoulders

to establish an unwritten system,

distinguishing the men from the boys.

I accepted those deposits

like an empty piggy bank

swallowing coins,

digesting them in my glass frame.

The body is the institution

where pain is traded.

At twelve, no one teaches you

tolerance is inherited in language.

When I had no voice

I made my mouth

a vault of echoes

sealed up like ghosts

on my tongue,

because silence is still

a choice—a transaction

between one body and another.

John Salimbene is a writer and MFA student based in New Jersey. He studies creative writing and holds an assistantship at William Paterson University. He's been a finalist for the Tom Benediktsson Award for Poetry and currently serves as the poetry editor for Tint Journal. His poems can be found or are forthcoming in giallo, Bodega, Small Orange, Voicemail Poems, queerbook (a 2020 anthology), and elsewhere.

Elizabeth SylviaOn Learning that Kim Kardashian Exceeded her Water Allowance by 232,000 Gallons in June

The guide pauses to tell her group

that when Marie Antoinette

walked these paths

Versailles swallowed

as much water

in one day

as Paris

used in a month.

A likeness of the sun god

rises in the gardens’

central pool,

barely harnessing

his frenzied horses

of the dawn.

L.A. glistens

with elsewhere’s water.

Snow off the Sierras

misting the carpets of lawn,

collecting on the leaves

of imported citrus, every fruit

a globe bursting with juice.

At Versailles, too,

oranges were grown.

Elizabeth Sylvia is the author of None But Witches: Poems on Shakespeare’s Women, winner of the 2021 3 Mile Harbor Press Book Prize and a Small Press Distribution bestseller. She has been a semi- or finalist in competitions sponsored by DIAGRAM, 30 West, and Wolfson Press and has been published in over 30 different literary magazines. She is a reader for SWWIM Every Day. elizabethsylviapoet.net